Research proves lasting brain damage in patients who battled with COVID-19. We have witnessed the damage coronavirus has done to our bodies. However, the most troubling is the damage to the brain. Recently, many studies documented long-term brain damage in more than a quarter of the 140 million Americans infected. And unfortunately, it did not matter how severe the illness was when infected.

Unfortunately, studies warn that the healthcare system will eventually become strained due to the amount of treatment needed for those with long-term brain injury. As a result, understanding the origin and treatment of COVID-19-related brain injury is a high priority.

The Results of COVID-19-related Brain Injury

The NYU Grossman School of Medicine assessed the cognitive function of COVID-19 patients six months after hospitalization. Shockingly, 90% of the cohort reported at least one neurological symptom. And out of those who did not experience neurological complications while hospitalized, 88% reported cognitive symptoms.

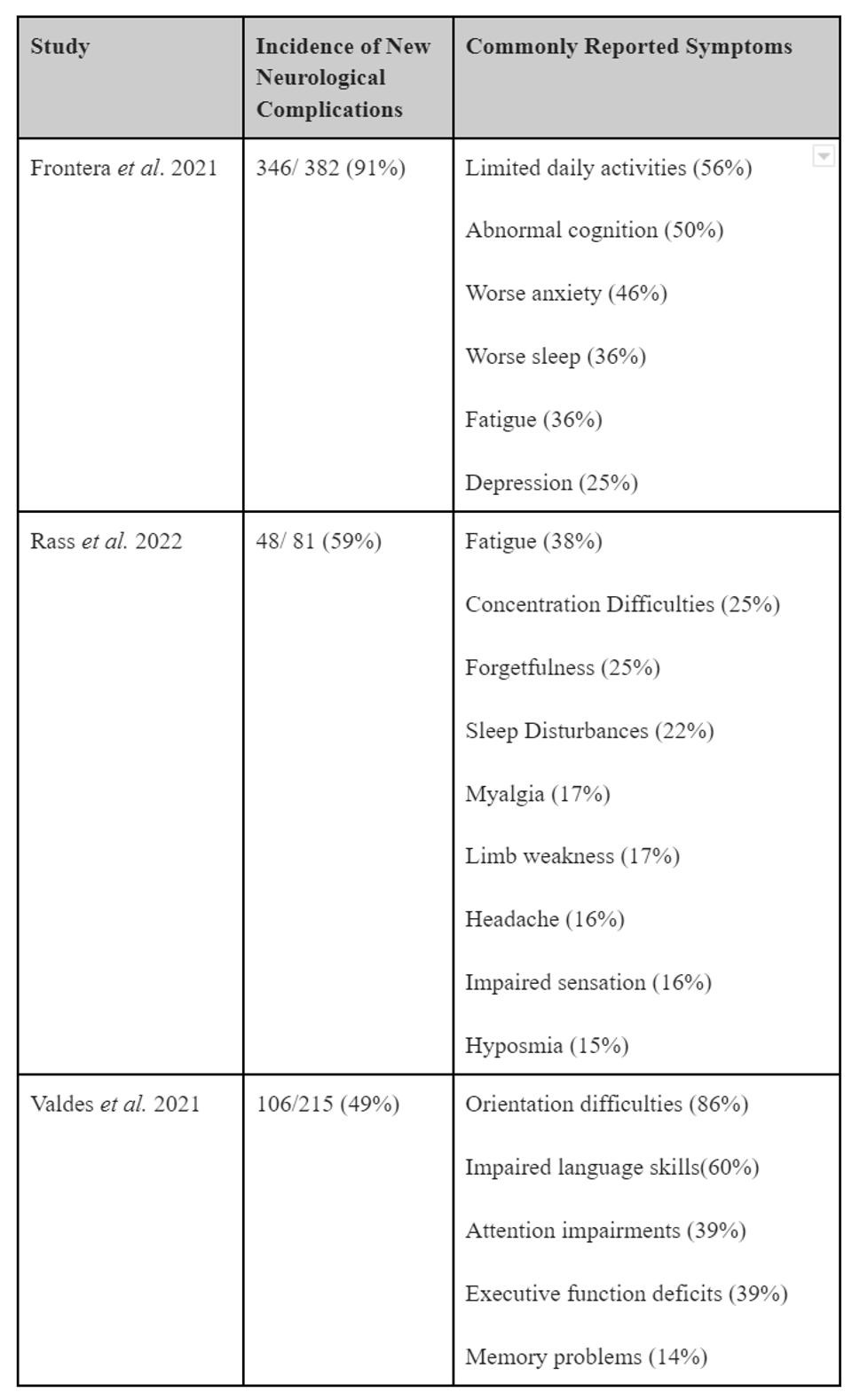

The cognitive impairments witnessed were separate from the damage caused by the lack of oxygen to the brain during hospitalization. In addition, patients who recovered from mild or asymptomatic infection may develop complications later, which may not be apparent at first. The table below summarizes the incidence of new neurological complications following hospitalization.

Furthermore, a neurologist diagnosed more than half of the participants of the NYU study with encephalopathy. Encephalopathy – a general term describing a disease that affects the function or structure of your brain. There are many types of encephalopathy and brain disease. And those diagnosed with encephalopathy had a higher incidence of strokes and seizures. Additionally, 21% had symptoms related to oxygen starvation related to COVID-19 damage to the lung or heart.

Lasting Brain Damage

Next, the study showed a correlation between neurological complications and an inability to return to daily activity after six months of the initial infection. Those who experienced neurological complications while hospitalized for COVID-19 were twice as likely to perform poorly on cognitive assessments than those who didn’t. For instance, over 50% reported being unable to return to daily activities, and 59% of those previously employed cannot return to work.

Another study revealed a disturbing fact for Black patients. Sadly, patients who were Black, unemployed, or had fewer years of education were likely to perform worse on a cognitive assessment six months after hospitalization than any other demographic.

This research proves that we must focus on the long-term effects of COVID-19 and possible treatment.