There’s good and bad news on the prostate cancer front. We’ll start with the disturbing statistics: This form of cancer is the most commonly diagnosed and the second most common cancer killer in men. Roughly 165,000 men receive a prostate cancer diagnosis each year; of that number, about 30,000 die.

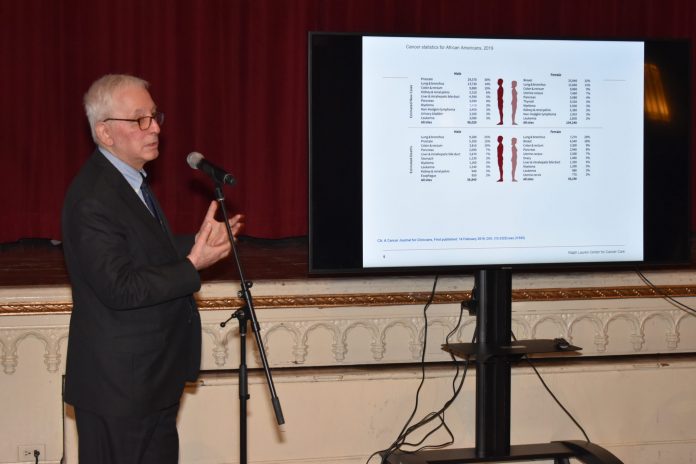

For our men, it’s “the same story, only a little worse,” said Lewis Kampel, M.D., medical director of the Ralph Lauren Center for Cancer Care in New York City, New York, at the Third Black Health Matters Health Summit, held at Riverside Church in Harlem, New York, earlier this month. “The likelihood of getting prostate cancer is more than one and three-quarters times higher if you’re an African American man. The likelihood of dying is more than two times higher if you’re African American than in non-Hispanic white men. If you’re a Caribbean man of African descent, your risk of getting prostate cancer and dying from prostate cancer is even higher than in African American men. These numbers should raise red flags. People should be up in arms.”

We don’t know all of the reasons for these disparities, though that’s why the Ralph Lauren Center was established: to tackle disparities seen in Harlem and surrounding communities. What we do know, according to Kampel, is that genetics play a factor. Beyond that, the environment, a high-fat diet, access to care and a cultural resistance to screening also could contribute.

We also know prevention is difficult. Men with early prostate cancer typically don’t have symptoms. “Most of symptoms men have are due to non-specific aging,” Kampel said. In other words, benign prostate disease and enlargement, also very common in black men.

This is why Kampel recommends screening for men having symptoms, including digital rectal exam, which picks up large tumors, and the controversial PSA test. In spite of guidelines directing PSA testing after age 55, African American men should start being screened a full decade and a half earlier, at age 40, Kampel said.

In fact, several large studies show screening reduces prostate cancer mortality, though the percentage of black men in those studies was quite low, only 3 percent to 5 percent. This stresses the importance of including more black men and women in trials.

It’s true we aren’t well represented in clinical trials. Experts attribute the lack of representation to everything from a distrust of the medical establishment to unconscious bias by white doctors when dealing with African American patients.

The solution to this lies in “addressing unconscious bias in medical training,” Kampel said. “Particularly in the cancer world, we need more African American doctors. I see student populations becoming more diverse, but for some reason, in medical oncology, it’s not a practice that appeals to African Americans. We need to make an effort to recruit them. If you see a team of doctors with diversity, the patient is much more comfortable and has more confidence in that team.”

If that team advocates for more participation in studies, especially prostate cancer studies with a focus on screening, so much the better.

“Screening works,” Kampel said, for detection and therapy. “The earlier the treatment the better for outcomes and side effects.”

That treatment includes active surveillance if the cancer isn’t aggressive and a man’s PSA is low; localized surgery and radiation, which could cause temporary urinary control issues and sexual dysfunction; or anti-hormone therapy, where the cancer is treated by reducing a man’s testosterone levels.

Now here comes the good news. “Cancer disparities in general are narrowing,” Kampel said, citing better access, better medical techniques and better information.

There’s even more reason for optimism in the face of a prostate cancer diagnosis. “African American men seem to do as good as or better than non-Hispanic white men with many of the treatment options,” he said.

And Kampel shared this final helpful observation to the women in the audience gathered at the health summit: Have your man’s back. “Women play a very important role in the management of prostate cancer,” he said. “Very often women are key in seeing their men through the difficult and challenging path prostate cancer patients follow.”