Protecting his health never entered the mind of James Young II during his 20s and 30s.

Exercise ended with his school years, and his diet largely consisted of fast food and microwaveable meals. He was also a heavy smoker and frequently met friends for a beer after work.

By 2006, he was progressively gaining weight, but blamed it on his beer consumption and poor eating habits. His legs were also swollen. Young didn’t realize it, but he was a retaining fluid, a symptom of heart failure.

Young also found himself out of breath after climbing stairs, but he just assumed he was out of shape. By late 2010, Young’s breathlessness during exertion had worsened. At one point, he coughed up phlegm mixed with blood, and the skin on his legs was unusually pale, a result of inadequate circulation.

He still didn’t go to the doctor.

“I thought it would just go away,” said the graphic designer from Detroit who didn’t have health insurance at the time. “Deep down, I think I was afraid of learning the truth.”

By summer 2011, Young had persistent coughing convulsions and difficulty climbing stairs. He felt like he couldn’t breathe when lying down.

“I couldn’t sleep because I was afraid I wouldn’t wake up,” Young said.

The symptoms finally convinced Young to see a doctor, who diagnosed him with very high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, pneumonia and kidney disease. He was prescribed several medications and ordered to come back every week for monitoring.

That monitoring revealed Young had heart failure, a chronic, progressive condition in which the heart is unable to pump enough blood to meet the body’s needs. At the time of his diagnosis, Young’s heart was operating at only 30 percent of its function. He was prescribed additional medication, but didn’t process the seriousness of his condition.

Less than two months later, Young was admitted to the hospital, where doctors found his heart had dropped to 20 percent of its function.

“I’ll never forget when the cardiologist said to me, ‘James, if had you waited one more week, you would have been dead,’” he said.

The health crisis forced Young to quit smoking and overhaul his diet, eliminating sugary drinks, alcohol and fast food. He has made healthy swaps, replacing bacon or ham with kale sautéed in olive oil to serve with eggs for breakfast.

“As I began to get healthy, I didn’t have an appetite for fast food anymore,” he said.

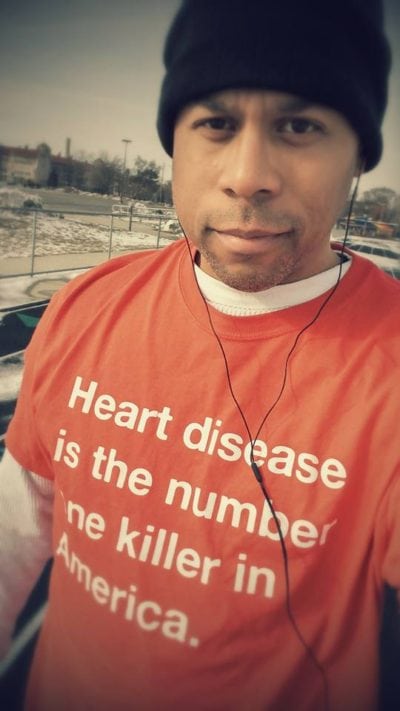

By November 2011, he was strong enough to take short walks. Soon he moved to the local high school track, pushing his almost daily sessions longer, sometimes going twice a day, working himself up to as much as 11 miles.

“I realized I had done so much damage to myself that I had to introduce my body to a whole other way of living,” said Young, who is now 45. “The track became a substitute for the barstool, and I got support from others out there.”

Nearly 6 million Americans suffer from heart failure, and studies have shown that African Americans have the highest risk for developing the condition. Young also has a family history of heart disease and diabetes.

“It was so common in my family that it seemed like part of life you couldn’t do anything about,” he said.

His father died from complications of congestive heart failure and type 2 diabetes in 2014.

“I wanted so much for my father to be inspired by my health success and realize he could experience the same, but he wasn’t willing to change,” said Young, who no longer requires prescription medication. “I want to inspire others to change their life so that they can avoid what I went through.”

Young is sharing his story through the American Heart Association’s Support Network. As an AHA Heart Failure Ambassador, he also spoke about his experience to doctors and researchers last fall at the AHA’s annual Scientific Sessions in New Orleans.

“It’s important to engage doctors on all these issues so that they can better work with patients to get at the root causes of the issues and better motivate them toward recovery,” he said. “Doctors always asked how I was feeling physically, but not how I was feeling emotionally. I had to figure out what was eating me, before I could deal with what I was eating.”

From American Heart Association News

Detroit Man Transforms Lifestyle to Overcome Heart Failure