“I’ll have time to work on it.”

“It won’t happen for some time from now.”

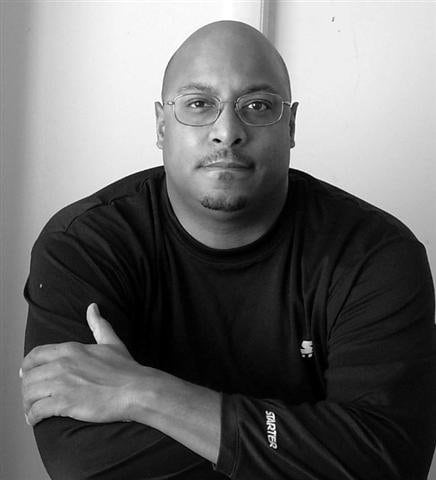

That was my denial when I was told about a year ago my A1C had reached the levels of diabetes. It was just over the range, so I still had a chance to work on it with diet and exercise. My doctor had been checking my A1C since 2010 as a part of my regular blood workup, so we were ahead of the game. I had mentioned that diabetes was a family trait, though I only knew of it coming at an older age; my dad in his late 60s and my mother’s brother in his 70s. I have since learned that I have a cousin on my mother’s side who was diagnosed with it in his early 30s. I was 49.

After my bad A1Cs, I had an appointment with a diabetic management adviser, initiated by my insurance provider. I walked in, sat down and she handed me a glucose monitor—oh joy. It’s easy to use. The pain the lancets to prick your finger cause can be more or less unpredictable, depending on how much they puncture the skin. The good news: My numbers were good during the day. The bad news: My levels were high when I woke up every morning, settling in between 165 and 181. The adviser and I opted for a prescription, a pill called Metformin, to see if it would help.

I tried it for a while and it worked, but I realized I was still eating the same way I’d been eating before my diagnosis. I told the adviser I would hold off on continuing the Metformin to see if I could do without it.

I continue to check my blood glucose levels as soon as I get up out of bed, before eating, to determine how high they are. I have good mornings—and bad ones. I adjust my breakfast to try not to push it up real high, like, over 200. I follow up most evenings before dinner, when my level is normal, 98 to 110.

What’s more difficult for me is adjusting to the change in what—and when—I eat. Carbs are key in maintaining my health. The more carbs I take in, the higher my sugar level rises and my pancreas and liver, working together, will not process them to keep my glucose level normal.

I can still eat carbs; trying to cut them totally is not a good idea. If I eliminate them completely, and then have some at a later time, it may cause my body not to process them properly.

My challenges are concentrating on not eating late at night out of habit and becoming more active. My job keeps me at a desk during the day, so I have to motivate myself to do something active after work. It can be as simple as going for a short walk. Weight loss helps reduce blood sugar levels, so diet and exercise are necessary.

Earlier in my diagnosis, I had to attend a one-time, all-day seminar mandated by my insurance. It was designed to educate people with diabetes and give us ways to take care of ourselves and adjust to this life-changing challenge. The adviser stressed one important thing: She said, “You are not a failure!”

To be honest, I did not see myself as a failure, because I expected to develop diabetes based on my family history. I have watched family members, especially my dad, have poor blood circulation, which could lead to complications like amputation or blindness. It just happened to me so fast! I kept putting caring for myself to the side.

Now I just remind myself that everyone’s body is different. Having diabetes is a life change and style unique for you. It’s all about balance. With balance, you can enjoy things, just in moderation.