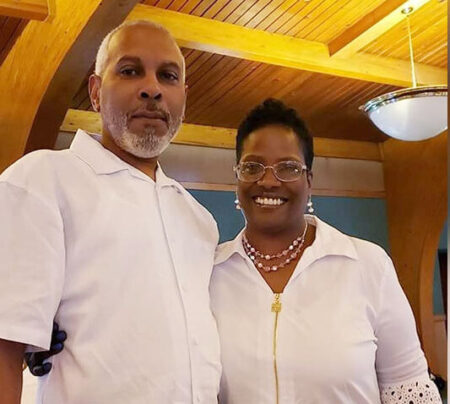

When Vickie Whyte began experiencing issues with her eyesight in 2007, she wasn’t alarmed. “I thought I’d see an eye doctor and get my prescription updated,” she says. But a few months later, when she hadn’t yet made the appointment and her symptoms were getting worse, a co-worker persuaded her to make the call.

By then, Whyte was starting to worry. “I was seeing black spots and wasn’t able to see out of my right eye,” she recalls.

Her appointment with an eye doctor ended with a recommendation to see an ophthalmologist who suspected multiple sclerosis, a diagnosis that was confirmed soon after by a neurologist at Whyte’s local hospital.

Thinking back, the Detroit resident admits to minimizing her symptoms. “I was treating it more as a joke,” she says, noting that her eye issues and periodic challenges with walking were signs that something wasn’t right.

Multiple sclerosis is a chronic disease that attacks the nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord as well as the optic nerve. Considered an autoimmune disease, MS causes inflammation and damage of myelin, a protective covering on nerve cells that helps them conduct electrical signals. As a result, the electrical impulses needed for the nervous system to communicate with the body don’t travel properly through the nerves.

Whyte was diagnosed with a form of the disease known as relapsing-remitting MS, characterized by symptoms that periodically flare up but then subside.

Like Whyte, many individuals with MS experience optic neuritis, a condition in which the optic nerve that connects the eye to the brain becomes inflamed. Optic neuritis is often the first symptom of the disease. Other symptoms may include muscle spasms, weakness, numbness and extreme fatigue.

Whyte’s diagnosis left her “scared to death.”

“I was angry and frustrated and I cried a lot,” she says, admitting that she made the mistake of turning to the internet for information about the disease. At one point, Whyte became so depressed that she contemplated taking her life.

“I secluded myself from friends,” says the self-proclaimed people person.” “I knew I needed to get help so I could take care of myself and my family.” Whyte, who has 4 children, including a son who was two at the time of her diagnosis, says antidepressants helped. And when she discovered that one of her MS medications might be adding to her depression, she sought a new one.

“Within 60 days I was feeling so much better on the new medication. It was a pill instead of a daily injection.”

After that, there was no holding her back.

“I made a decision to do more to help others living with multiple sclerosis,” she says. Inspired by a speaker at an MS seminar who told the audience, ”You can do whatever you want with MS,” she took the message to heart. “That speaker motivated me,” says Whyte, who is now a speaker at various MS events.

Whyte tells her story without holding back. “I talk about depression. It’s real. It’s there. It needs to be talked about,” she says. “As long as one person can understand my story—hear my story—and connect with it, I’m happy. It’s my way of giving back.”

Another important message she shares is an extension of the one that first inspired her: “You can do whatever you want to do with MS, but do it in moderation.”

Whyte speaks from first-hand experience as she, like many MS patients, battles extreme fatigue.

“Fatigue is one of the most common symptoms of multiple sclerosis, occurring in up to 90 percent of persons with MS,” says neurologist Tiffany Braley, M.D. “Fatigue can occur at any stage of the MS course and, because it can significantly impact daily occupational, social and family function, it is an important symptom to identify and manage early.”

“When I was diagnosed, I had a young child,” says Whyte. “I had to learn to do things in moderation. For example, I don’t do well when the weather is hot, so now when I’m at my son’s football games, if I get too hot, I go to my car and sit in the air conditioning until I feel well enough to go back and watch.”

In keeping with her desire to help other MS patients, Whyte participates in clinical trials and studies that focus on multiple sclerosis. “I’m committed to these studies because without us, how do they know what will work?”

One study, known as the COMBO-MS trial, brought Whyte to Michigan Medicine. This clinical trial, led by Braley and Anna Kratz, compares the effectiveness of telephone-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy and a medication known as modafinil, either alone or in combination, to treat MS fatigue.

“While both treatments have been shown to help MS fatigue, these treatments have never been studied together to see if their combination may lead to more benefit,” says Kratz.

“Pharmacological treatments, cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness-based strategies, exercise regimens and dietary modifications have all been studied for MS fatigue with some promise,” says Braley. “Addressing sleep problems is another important strategy that often gets overlooked, and is a main research focus at our MS Fatigue and Sleep Clinic.”

The Center is a first of its kind clinic that is focused solely on the evaluation and treatment of fatigue and sleep problems (which often contribute to fatigue) in individuals with MS.

Despite much progress, says Braley, “We still need more information on how to tailor these treatments to each patient, depending on their fatigue type and other characteristics. MS is a highly individualized condition, and we cannot continue to rely on a one-size-fits-all approach to fatigue management.”

Whyte says she had energy in the mornings, but by 2 or 3 in the afternoon she was exhausted. The COMBO-MS study was good for the 50-year-old for many reasons. In addition to medication that helped her combat fatigue, Whyte learned the importance of exercise and healthy breathing techniques through cognitive behavioral therapy.

“I started exercising more—walking up and down the steps and riding my recumbent bike. Before I knew it, it was 7 p.m. and I wasn’t exhausted,” she says. “Exercise gives you more energy. I make myself do it because it works. The breathing techniques really calm me when I’m feeling overwhelmed. They help me think more clearly,” she says, noting that she’s brought them into her everyday life.

Now symptom-free, this multiple sclerosis warrior is continuing to exercise, practice deep breathing and support her MS family. “I tell them, talk with your doctor, get on the medication you need for MS and depression if necessary.”

Whyte says she has to stay healthy for her MS family. “I’ve gotten calls from other MS patients looking for advice. I try to give them reassurance and resources for help. One thing we have in common is MS. It’s OK. You’ll have good and bad days. Just do the best you can. Don’t stop. My feeling is, I’m still young. How can I make things better each and every day?”

From Michigan Health